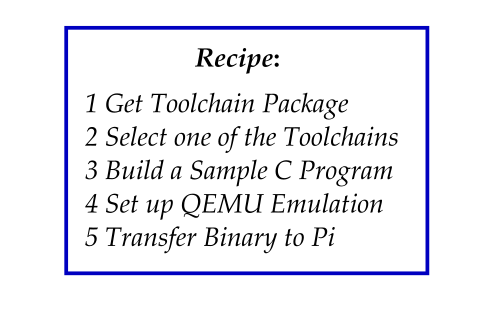

This is about how to set up a cross compiler for the Raspberry Pi and use it for building target executables from C source code. Additionally, we are going to talk about how to set up userspace emulation – enabling you to execute target binaries on your host system transparently.

We will also look a bit into the details of the cross-toolchain provided on Github and what is contained with it, just out of curiosity.

Let’s jump right into it!

1 Get the Raspberry Pi Toolchain

In order to be able to compile C code for the target system (that is, the Raspberry Pi), we will need two things:

- A cross compiler and its associated tools (cross-toolchain)

- Standard libraries, pre-compiled for the target

You can get both of them from the Raspberry Pi Tools repo on Github. Let’s create a working directory first:

sudo mkdir /opt/pi

sudo chown $(whoami) /opt/pi

Clone the tools repo into your working directory:

cd /opt/pi

git clone https://github.com/raspberrypi/tools

You will end up with a tools directory that contains the C compiler(s) and everything:

$ file tools/arm-bcm2708/[...]/arm-linux-gnueabihf-gcc-4.8.3

[...] ELF 32-bit LSB executable, Intel 80386, [...]

You will also find different pre-compiled versions of the C library there; this one, for example:

file /opt/pi/tools/arm-bcm2708/[...]/libc-2.13.so

[...]/libc-2.13.so: ELF 32-bit LSB pie executable, ARM, EABI5 version 1 [...]

If we take a closer look at the two listings above, we notice a difference in the output of the file program: While the first one, applied to the gcc executable, states that this is to be run on your x86-compatible machine, the second listing clearly reveals you cannot do this for the libc library.

All of that is an indication that we are actually dealing with a cross-toolchain. Great start!

2 Select a Toolchain to use

After downloading you will notice there’s more than one toolchain folder inside of the tools folder. Here’s a list of what you can find there:

arm-bcm2708hardfp-linux-gnueabi

arm-bcm2708-linux-gnueabi

arm-linux-gnueabihf

arm-rpi-4.9.3-linux-gnueabihf

gcc-linaro-arm-linux-gnueabihf-raspbian

gcc-linaro-arm-linux-gnueabihf-raspbian-x64

After resolving all symlinks, it boils down to three cross-toolchains we can choose from. Here are the corresponding gcc executables:

/opt/pi/tools/arm-bcm2708/arm-bcm2708hardfp-linux-gnueabi/bin/arm-bcm2708hardfp-linux-gnueabi-gcc

/opt/pi/tools/arm-bcm2708/arm-bcm2708-linux-gnueabi/bin/arm-bcm2708-linux-gnueabi-gcc

/opt/pi/tools/arm-bcm2708/arm-rpi-4.9.3-linux-gnueabihf/bin/arm-linux-gnueabihf-gcc

They all can build binaries for the target architecture, that’s for sure. But what are the differences, and which one should you use for compiling your code?

According to the Linaro GCC FAQ Page, the toolchain names follow a well-known theme. I’ve prepared a table that shows the parts between the “-“ sign, each in its own column:

| Target | Vendor | ABI | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| arm | bcm2708hardfp | linux-gnueabi | for 32-bit host |

| arm | bcm2708 | linux-gnueabi | for 32-bit host |

| arm | rpi-4.9.3 | linux-gnueabihf | for 64-bit host |

In the table, bcm2708 is the name of the device family of the Raspberry Pi’s SoC (BCM2835 in case of A+). The term gnueabi, according to the Linaro FAQ, is just an arbitrary name for an Application Binary Interface (ABI) version that came after gnu. It is basically short for what they call AArch32.

Eventually, they will all produce binaries for the Raspberry Pi. The difference is how much the result is optimized to your target system. From the naming alone, I would assume the only difference is how the compiler deals with floating point numbers, i.e. whether it utilizes the Pi’s (hardware) floating-point unit or not.

But actually, I don’t think it’s that simple: There are hundreds of possible tuning parameters which were selected while building these compilers. There is a neat description on the Raspberry Pi forums: Difference between arm-linux-gnueabi and bcm2708?.

As a side note: You may have trouble using the first two compilers on your 64-bit host system and get an error message that looks like this:

error while loading shared libraries: libz.so.1: cannot open shared object file: no such file or directory.

This is a rather cryptic description; Chances are, you’re just missing the appropriate x86 libraries and that’s the reason they cannot be found. You can fix this by either:

- just using the third one, which is 64-bit :) or

- installing the needed library on your host system (refer to AskUbuntu: Error while loading shared library libz.so.1 while cross compiling for arm-linux)

Long story short: You can take any of the toolchains offered, depending on your host system’s architecture. For 32 bit, you can choose from two of them.

3 Build a sample C program

At this point we should be able to compile a Hello World program, to see if the toolchain works:

#!/bin/bash

/opt/pi/tools/arm-bcm2708/arm-rpi-4.9.3-linux-gnueabihf/\

bin/arm-linux-gnueabihf-gcc -static -x c - <<EOF

#include <stdio.h>

int main(void)

{

printf("Hello Cross Compiler!\n");

return 0;

}

EOF

file a.out

To give it a try, you can copy the entire snippet into a shell script and execute it. In case you are wondering what the EOF markers are about: The C code is embedded using a technique called the Here Document. Actually, that’s just an unimportant detail that saves us from having to create another c file. So, don’t worry too much about it if it seems confusing.

Anyways, the script will generate an executable called a.out and show some details about it:

a.out: ELF 32-bit LSB executable, ARM, EABI5 version 1 (SYSV),

statically linked, for GNU/Linux 2.6.32, with debug_info, not stripped

Note that the resulting executable has been linked statically against the standard library. This makes it easier for us to deal with dependencies in this example. The principle is the same for dynamic linking, it’s just a bit more complex to set up (because you have to deal with selecting the loader and such).

4 Set up Qemu User Mode Emulation

You can see from the output above that we are dealing with an ARM executable. That also means we cannot execute the program on our host machine. In order to fix that, let’s set up a way to emulate the ARM on our host machine.

That approach is really interesting because it makes the emulation process transparent to you. Upon installation, Qemu registers a set of binary formats (binfmt) with the Linux kernel.

Let’s install the package(s) needed for Qemu:

(sudo) apt-get install qemu-user

You can verify installation by inspecting the output of update-binfmts --display:

$ update-binfmts --display | grep "qemu-arm " --after-context 7

qemu-arm (enabled):

package = qemu-user-binfmt

type = magic

offset = 0

magic = \x7f\x45\x4c\x46\x01\x01\x01\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x02\x00\x28\x00

mask = \xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\x00\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xfe\xff\xff\xff

interpreter = /usr/bin/qemu-arm

detector =

There is a previous article on this blog about some experiments with Linux bin formats you may find interesting in this context: Deardevices: Linux Shebang Insights.

Executing the target binary should now be as easy as:

$ ./a.out

Hello Cross Compiler!

5 Transfer Binary to the Pi and execute it there

Executing on the target should work just as well. Let’s copy the binary and execute it via ssh:

scp a.out pi@pi:~/

ssh pi@pi "~/a.out"

Hello Cross Compiler!

That’s it! We are done.

Conclusion

In this article, we have looked a bit into the Raspberry Pi tools repository and selected a cross-compiler we then used to compile an executable for the target system. We have set up QEMU User Emulation so we could run the compilation result on our host Linux.

Where to go from here?

To keep it simple for now, we haven’t messed with dynamic linking yet. That’s indeed a limitation for practical use so we may talk about it in another article on this blog.