After talking about decoupling at the object level in part 1 of this series, we are going to explore another method in this article. This will be based on yet another stage of the software build process – the linking.

Note: This is a series of three articles. You can find the other ones here: Part 1, Part 3.

The previous article was more or less based on the concept of Seams, introduced by Michael Feathers in Working Effectively with Legacy Code. So let’s see what he has to say about Link Seams:

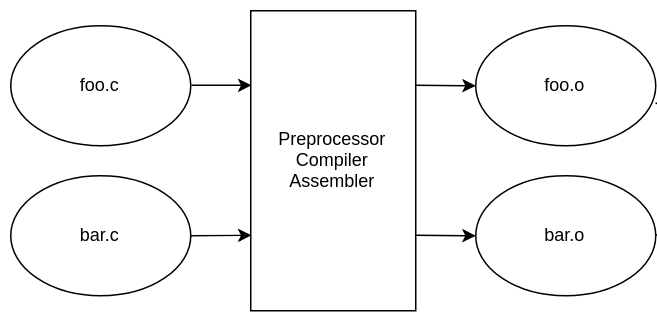

In many language systems, compilation isn’t the last step of the build process. The compiler produces an intermediate representation of the code, and that representation contains calls to code in other files. Linkers combine these representations. They resolve each of the calls so that you can have a complete program at runtime.

Linking Overview

Here, Feathers does a great job describing how the linking works. For C and C++, this is enough to know for now.

You can see a flowchart of the process below. Each .c file is compiled individually as a compilation unit. This means the compiler outputs a .o object file for each of them:

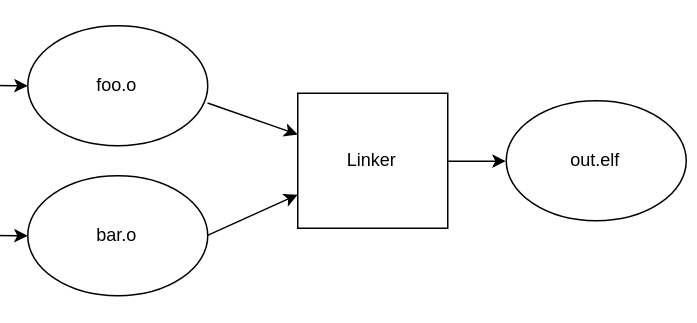

All object files are then passed on to the linker whose job is to put everything together – in order to get an executable program:

One important part of linking is to look for unresolved symbols needed by objects (function names, for example) and to try to satisfy those using symbols exported by other objects.

Exploiting the Linking Process

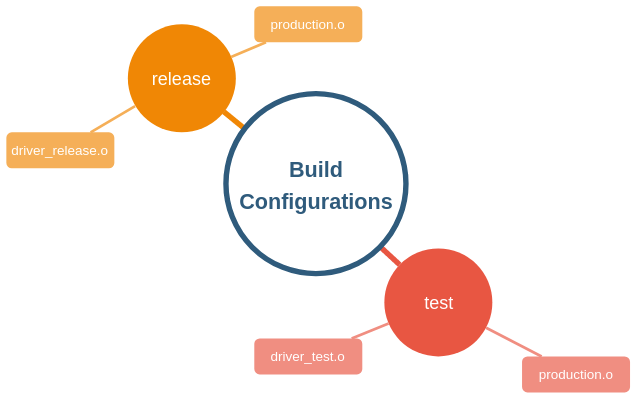

As described by Feathers, we may exploit this process by offering different sets of symbols, based on what our build configuration looks like.

Let’s take a look at this Makefile snippet to get the idea:

release.elf:

gcc driver_release.o production.o -o release.elf

test.elf

gcc driver_test.o production.o -o test.elf

There are two different targets, one for each build configuration we wish to maintain:

release: results in a shippable executable.test: contains debug code for testing that should never go out to the customer.

As shown in the diagram below, to build each of the two ELF executables we pass the exact same object file production.o to the linker in either case.

The linker now strives to find matches for symbols demanded by production.o. For that, it happily considers any object file it is offered. Assuming driver_release.o and driver_test.o adhere to the same API convention, the linker doesn’t see the difference and builds two different configurations for us.

The fact that we were able to switch implementations, depending on the build configuration suggests some level of decoupling between the units used in the example above.

Conclusion

This decoupling method has no runtime cost at all, which comes at the price of decreased flexibility compared to the approach taken in part 1. To switch over to a different configuration, you will at least need to re-run the linker. You do not need to recompile your objects though – This may improve build time significantly, depending on the size of your project.

Speaking about runtime cost: there might be some kind of indirect runtime cost for this solution. Because functions are implemented within different compile units, the compiler doesn’t have the big picture that would be useful for optimization. This might be compensated by Link Time Optimization (LTO) though.

In the next and last article, you will find the third method (preprocessor) as well as a compact overview of all three methods we have talked about so far.