When creating Embedded Software, system complexity that grows over lifetime makes it increasingly harder to reason about certain behaviors of the program. As always in engineering, it helps to divide one big problem into several smaller problems in order to be able to eventually solve it. This is what this article is all about.

Note: This is a series of three articles. You can find the other ones here: Part 2, Part 3.

In his book Working Effectively with Legacy Code, Michael Feathers introduces the idea of a seam as:

a place where you can alter behavior in your program without editing in that place.

Although originally intended as a means for getting legacy code under test, we will use this idea as a guide for designing software in the first place. This is a key aspect of loose coupling, after all: the ability to make changes in units of production code without changing the units themselves.

Before diving into the details, let’s talk about units first.

Units and their Dependencies

Let’s say you are about to start a new embedded project.

You may not even think about designing a system separated into different units at all – and that’s perfectly fine. When building prototypes, we want to see whether something is working, especially whether our software plays well together with the hardware.

In that phase of a project, it’s probably not that important to make a distinction between different units at all. Everything may be coupled very tightly, maybe even within just a single unit or module (Forgive me that I use the terms unit and module interchangeably in here).

As the project grows, it becomes more and more complex, and we usually want to do something about that to stay in control. What we can do is split up the code and put it into different compilation units (i.e. .c/.cpp files) to reach some kind of logical separation.

These logically separated pieces of code we will call unit for the rest of this article.

Let’s imagine a project about:

- Measuring a voltage level using an ADC,

- Averaging that number over time and

- Showing the result on an LCD.

Additionally, via the serial port, the user should be able to:

- See the averaged number every few seconds and

- Start and stop the sampling process by issuing a command.

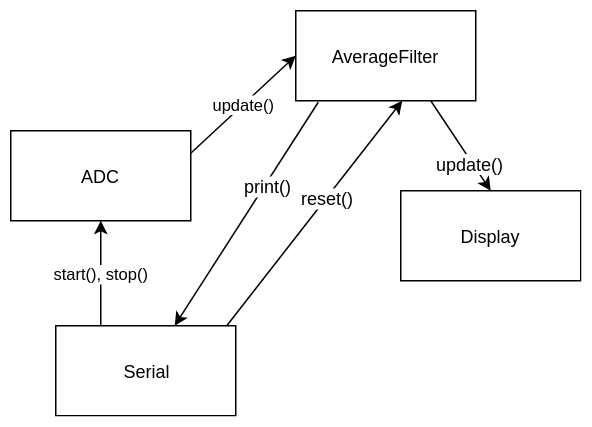

From that description, we can divide the system into four units: ADC, AverageFilter, Display, and Serial. The following diagram shows some dependencies between these units based on how they would probably communicate with each other. Does this make sense?

You can see from the diagram that all of these units are coupled somehow. An arrow here reads as depends on or includes a header file. AverageFilter depends on Serial because it calls its print() function.

Loosen the Coupling

At some point, we might want to replace one or more units by a different implementation – without any impact on the rest of the system. And without any impact here even means: without changing any of the other unit’s code. There are various reasons you might want to do that. For example:

- Switch averaging filters at runtime, depending on user configuration

- Swap the serial interface between RS232 and USB, depending on build parameters

- Replace the display unit by some stub in the test build

And here comes the tricky part: you cannot simply remove or replace units that are pointed to by a dependency. To make this possible, we need to decouple units from each other.

As the post title suggests, there are (at least) three ways to realize this in C and C++. We are going to take a look at the first one of them now.

Best Practice #1: Decoupling At the Object Level

This method is the most flexible one. At runtime, you pass a dependency into a unit. In C++, you would create an interface (an abstract base class) and let the unit implement it. Something similar can be done in C, by letting the unit depend on a set of function pointers.

The following snippet shows a C++ example for breaking up the tight coupling of the AverageFilter to the ADC unit:

class FilterInterface {

public:

virtual ~FilterInterface() {}

virtual void reset() = 0;

virtual void update(uint8_t) = 0;

};

class AverageFilter : public FilterInterface {

public:

void reset() override {

}

void update(uint8_t) override {

}

};

class ADC {

public:

ADC(FilterInterface& interface) : interface(interface) {

interface.reset();

}

void process(void) {

interface.update(42);

}

private:

FilterInterface& interface;

};

[...]

int main(void) {

AverageFilter filter;

ADC adc(filter);

while(1) {

adc.process();

}

}

The class ADC depends on the interface of type FilterInterface and stores a reference to it. Thereby it is agnostic to the concrete implementation passed in.

In C, we don’t have the concept of polymorphism (which is the mechanism that makes it possible to use concrete implementations transparently through base class pointers). You can always emulate it using function pointers, though:

typedef struct {

void (*reset)(void);

void (*update)(uint8_t);

} FilterInterface;

static FilterInterface interface_;

void ADC_init(FilterInterface interface) {

interface_ = interface;

interface.reset();

}

void ADC_process(void) {

interface_.update(42);

}

This tends to be a bit less explicit and more error-prone than the C++ implementation. It might still be worth it (and people actually do it: systemd, Linux drivers).

Conclusion

In the first part of the series, we’ve seen how to decouple units at the object level using Best Practice #1. This solution, no matter if implemented in C or C++, comes with a runtime cost while giving you the freedom of modifying dependencies at runtime as well.

In the upcoming second episode, we will investigate how to swap the serial interface in the context of our example system structure. So stay tuned!