This article is about creating a parser for HEX files, a format that is often used as an intermediate step for programming microcontrollers. Although there are – of course – implementations out there already, I would like to use this as a welcome opportunity to play around with some interesting approaches: Object Oriented Design Patterns, Finite State Machines (FSM) and Test-Driven Development (TDD).

We will start off with a brief definition of the HEX format. Based on that, we will develop a state diagram that shows the potential solution at a glance. From there, we will grow the implementation in C++ in a test-driven style.

The HEX format

HEX is an ASCII format for storing binary data (Wikipedia: Intel HEX). As an introduction, let’s take a look at a file containing two example records (taken from the Wikipedia article):

:100130003F0156702B5E712B722B732146013421C7

:00000001FF

That file consists of two records separated by a newline – the first one being a Data record:

:: Start Code10: Byte Count (0x10, 16 in decimal)0130: Address00: Record Type Data3F0156702B5E712B722B732146013421: payloadC7: Checksum

The second example record is of type End-Of-File (EOF):

:: Start Code00: Byte Count (zero)0000: Address (“typically” zero, says Wikipedia)01: Record Type EOF<no payload>FF: Checksum

Those two lines make up a complete and valid HEX file.

Requirements & Design

To define the scope of our parser, let’s set a few restrictions:

- We only care about one record, not an entire file.

- The parser has no knowledge of the restriction that only one EOF record per file is allowed.

- We plan to handle 16 bit addresses only (I8HEX) as this is enough for the program memory of the microcontrollers we’re targetting here.

To get a grasp on the problem, we will design a Finite State Machine (FSM) for the parser. While this may sound pretty fancy, it’s actually not too complicated and models the problem in a clear and concise way.

To get started, we need two things: a set of states and one or more inputs. We can define one state for each part of the record the parser expects:

- Start

- ByteCount

- Address

- RecordType

- Data

- Checksum

As the only input event, we’ll use a string of characters. Let’s call this newData. Note that this is already an optimization; passing in single characters would work as well. We’re going to explore that later in this article.

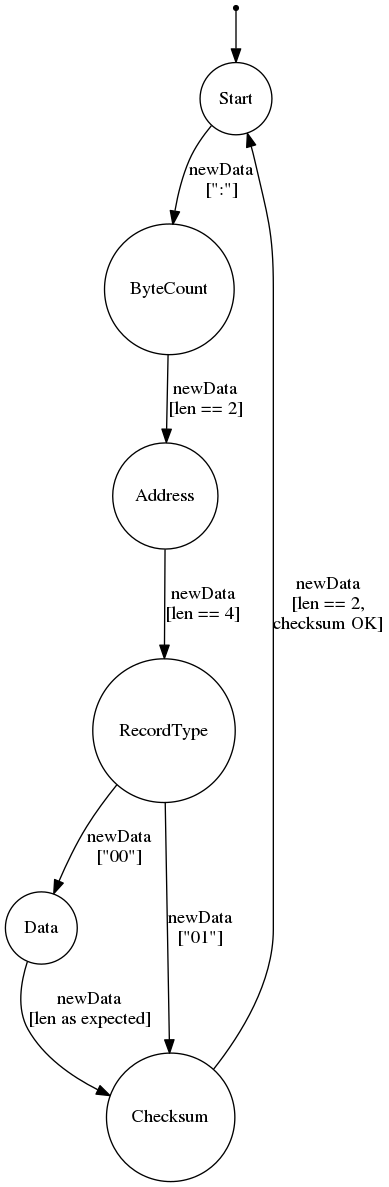

The state diagram in the following picture shows the design of the state machine. There you see states, connected via directed edges describing the transitions between them. The labels next to the edges contain the name of the input event as well as a condition that must be fulfilled for the transition to be made. To switch from Start to ByteCount, for example, we expect a : character. After that, the transition to the Address state is made only if exactly two characters are encountered.

For the sake of simplicity, there’s no error handling shown in this diagram. One way would be to add an Error state and define transitions from all other states for unexpected newData events.

C++ Implementation

For the implementation, we will utilize the object-oriented State Pattern. This will result in one class per state, all implementing a common interface that defines the input event as a method.

All these state classes are defined inside of a context class, HexParser. This enclosing class also keeps an instance for each of them, passing them a reference to itself at construction. Let’s take a look at the following listing that shows the definitions of the context class and one of the state classes, just to get the idea:

class HexParser {

public:

size_t newData(const char* inBuffer, size_t len) {

return currentState->newData(inBuffer, len);

}

private:

class BaseState {

public:

BaseState(HexParser& context) : context(context) {}

virtual ~BaseState() {}

virtual size_t newData(const char*, size_t) = 0;

protected:

HexParser& context;

};

class WaitForStart : public BaseState {

public:

WaitForStart(HexParser& context) : BaseState(context) {}

size_t newData(const char* inBuffer, size_t len) override;

};

[...]

WaitForStart waitForStart{*this};

WaitForByteCount waitForByteCount{*this};

WaitForAddress waitForAddress{*this};

WaitForRecordType waitForRecordType{*this};

WaitForData waitForData{*this};

WaitForChecksum waitForChecksum{*this};

BaseState* currentState{&waitForStart};

};

There’s a wrapper method HexParser::newData that dispatches to the currently active state class instance. This works in an elegant way: As each state object holds a reference to its enclosing HexParser instance, it may modify the currentState pointer at any given time.

The initial state is specified by the initial value of the currentState member – WaitForStart, consistent to the diagram above.

Demo usage:

HexParser parser;

parser.newData(":", 1);

parser.newData("10", 2);

// [...]

if (parser.recordReady()) {

parser.getRecordType();

parser.getData();

// [...]

}

// [...]

String Optimization

As mentioned above, the FSM has been designed to accept entire strings instead of just single characters. This enables us to walk through a given input string piece by piece and pass it into the parser:

const char* input = ":10010000214601360121470136007EFE09D2190140";

const char* pos = input;

size_t requestedCharCountPrev = 1;

size_t requestedCharCount = 1;

while(!parser.recordReady()) {

requestedCharCountPrev = requestedCharCount;

requestedCharCount = parser.newData(pos, requestedCharCountPrev);

pos += requestedCharCountPrev;

}

This use case is the reason why newData returns a size_t. Although no performance measurements have been done so far, this approach might have an advantage when a queue is filled by some interrupt service routine and we can just wait until enough characters are available.

In a follow-up article we might actually do real measurements to prove this solution better (or worse?) than a simpler one with void newData(char).

Conclusion

We have seen how to model a simple parsing challenge as a finite state machine and how to implement it in C++.

While the FSM is probably not the most optimal implementation in terms of processing speed, the corresponding state diagram precisely shows what is going on – so it has its own value for documentation purposes.

As you may have noticed, we haven’t talked about the TDD approach mentioned in the introduction at all. That’s because there is so much high-quality content about that topic on the internet already (e.g. Uncle Bob - The Cycles of TDD) – I don’t think I need to repeat that here. To see the result of the application of this method, please take a look at the file hex-test.cpp inside the hex-parser repo on github.

There you will also find a short demonstration of the parser (demo.sh).