Git is a powerful tool for versioning (not only) source code files. It is decentralized by design but also works perfectly for setups that rely on a central server. By using a standard pull/push workflow though, the central history can grow complex pretty fast. In this article we will look at a simple centralized git approach and try to come up with a solution for keeping the history clean and easy to understand.

TL;DR: Use git pull --rebase to incorporate changes from a central repository.

Example Setup

Let’s start by setting up a central git repository and creating two clones of it:

$ git init --bare repo

$ git clone repo clone0

$ git clone repo clone1

Next we’ll create a commit in repo clone0 and push it to the central repo via git push:

$ cd clone0

$ echo "line 0" > foo.txt

$ echo "" >> foo.txt

$ echo "line 1" >> foo.txt

$ git add foo.txt

$ git commit -m"Add first two lines"

$ git push

We are now able to replicate that commit to our second clone using git pull:

$ cd ../clone1

$ git pull

Creating a non-linear history

To establish a non-linear chain of commits, we will now make a change in clone1, commit and push it.

$ echo "line 0" > foo.txt

$ echo "" >> foo.txt

$ echo "line 1 (changed)" >> foo.txt

$ git commit -am"Change line 1"

$ git push

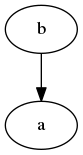

The local history of clone1 will then consist of two commits, let’s say a and b, linked to each other. Note that in the following graph, commit b refers to commit a (because it keeps the SHA1 hash of its parent).

Then we switch to clone0, modify line 0 and commit that change as well – but don’t try to push it yet.

$ cd ../clone0

$ echo "line 0 (changed)" > foo.txt

$ echo "" >> foo.txt

$ echo "line 1" >> foo.txt

$ git commit -am"Change line 0"

Before attempting to push that commit, let’s see what the central repo’s state is:

$ git fetch

[...]

$ git status

On branch master

Your branch and 'origin/master' have diverged,

and have 1 and 1 different commit each, respectively.

(use "git pull" to merge the remote branch into yours)

nothing to commit, working directory clean

As git status reports, we are now in a situation where the local and master branches have diverged from each other. To resolve that, we could just issue a git pull, as git suggests. So let’s give it a try:

$ git pull

Auto-merging foo.txt

Merge made by the 'recursive' strategy.

foo.txt | 2 +-

1 file changed, 1 insertion(+), 1 deletion(-)

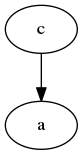

As soon as we accept the suggested commit message presented to us in our default $EDITOR, git will complete the merge of the two branches. The history will then look like this:

That’s exactly what is meant by a non-linear commit history. Technically of course, the result of the merge is perfectly fine. Our example file foo.txt is now a combination of the two changes we’ve made:

$ cat foo.txt

line 0 (changed)

line 1 (changed)

The issue here is just that nobody looking at the global history would even care about those points in time where somebody on the team incorporated the global state into his local copy. The sequence of commits would make a lot more sense to a reader of the log if it were linear. In fact, most projects I could find as an example on github do maintain a linear commit history 1.

Fix it

As long as the merge commit is not yet pushed to the central repo, we may undo the pull from above by resetting our local branch to the previous HEAD:

$ git reset --hard HEAD~

Now, instead of merging the remote master into our local one, we may choose another approach to bring those two commits together – rebasing:

$ git rebase origin/master

First, rewinding head to replay your work on top of it...

Applying: Change line 0

Using index info to reconstruct a base tree...

M foo.txt

Falling back to patching base and 3-way merge...

Auto-merging foo.txt

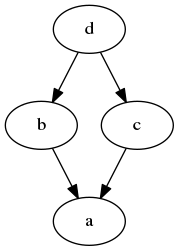

This results in a history that looks a bit different compared to the one from above:

We can now clearly identify the two commits b and c chained as if they were created one after another on the same branch. This is what people like to see by looking at a global history. So let’s push it:

$ git push

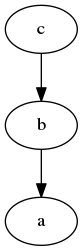

We can finish the entire procedure by pulling the commits into the other repo:

$ cd ../clone0

$ git pull

Note: the git pull command is in fact a fetch followed by a merge. To do a rebase instead of a merge, you may also just use git pull --rebase.

Why isn’t that the default behavior?

If it results in such a nice commit history in our central repository, why isn’t the --rebase option set by default for all pulls?

One reason might be the fact that rebasing involves rewriting parts of your local history. This makes the command harder to use than merging – you have to watch out not to rebase any commits that have been pushed to another repo already. This issue is described in great detail in Pro Git (Chapter Rebasing).

Besides that, we need to keep in mind that git is in fact designed to be a decentralized system. Linus Torvalds himself has explained that at Google Tech Talks in 2007. So the use case this blog article is based upon is actually not the most important one – in contrast to other version control systems like Subversion.

The third and final aspect I would like to highlight is something that is also described in the Pro Git chapter about rebasing. Sometimes people actually might have the need to keep track of everything that happend to a particular repo’s history. This would include each and every merge; history rewriting via rebase is not desired in such a case.

References

-

Examples of projects with a linear commit history: OpenWrt, Linux Kernel, Vim, GNU coreutils. ↩